A century ago today the men of the Canadian Corps made an assault on the village of Courcelette as part of the Battle of the Somme. This was a battle of firsts for Canada: it was the first time the Canadian Corps had led an attack, it was the first time anyone had gone into battle with tanks, it was the first time Canadian troops had liberated French soil and a French village, and symbolically it was the first time the French-Canadian 22nd Battalion Canadian Infantry had gone into battle, to help liberate that village. The village was captured with the assistance of those tanks, especially in the area of the Sugar Factory. And while Courcelette was taken on this day, the Canadian Corps would remain here for the next two months battling for positions like Zollern Graben, the North and South Practice trenches and finally Regina Trench and Desire Trench. By the time Canadian units pulled out in November 1916, more than 24,000 Canadians had become casualties: more than 8,500 of them killed and of them, over 6,000 missing – half of the names on the Vimy Memorial commemorate men who died at Courcelette.

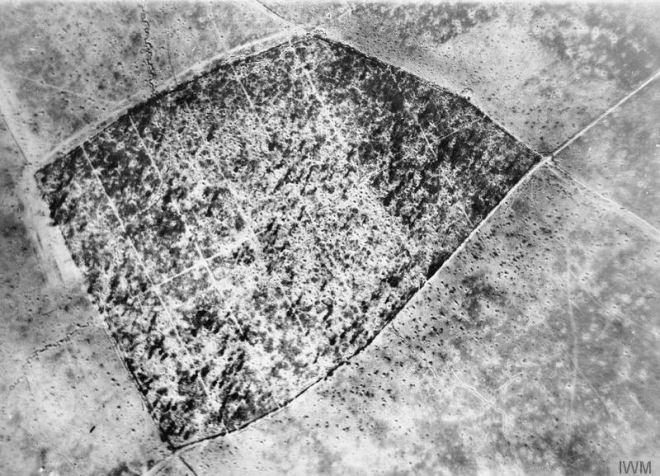

Sugar Factory, Courcelette

But for Canada, Courcelette is a forgotten battle. Despite its symbolic position in the history of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, despite the huge scale of the missing, few Canadians visit the village and the three cemeteries that surround it: Courcelette British Cemetery, Regina Trench Cemetery and ADANAC Cemetery… ADANAC is Canada spelt backwards. Canadian education groups and Canadian battlefield tours come to the Somme every year but they always visit the Newfoundland Park at the expense of Courcelette: which while the park is now run and maintained by Veterans Affairs Canada, it has no connection to the story of Canada in WW1 as the Newfoundland Regiment was part of the British Army, and Newfoundland itself was not part of Canada until after WW2. Even the local tourist authorities on the Somme invariably describe the Newfoundland Park as a “Canadian Battlefield”. Meanwhile the fields around Courcelette remain silent.

Courcelette aerial photo 1916

Today a handful of people will remember Courcelette, in the village and the cemeteries. There will be no big official ceremony, and possibly no official Canadian representation. A century on, Canada’s knowledge of the Great War is still over-dominated by Vimy Ridge and Canada’s sacrifice on the Somme in 1916 sadly appears to be a footnote in that war when it should be so much more.